#1: Jose Aldo

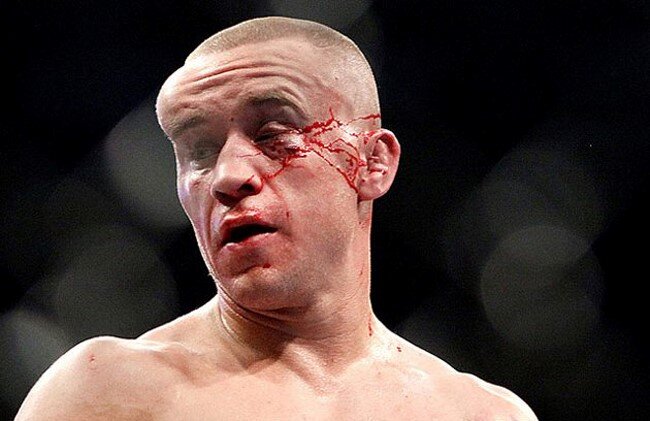

Photo by Josh Hedges/Zuffa LLC/Zuffa LLC via Getty Images

Jose Aldo and Chad Mendes gave each other 25 minutes of hell at UFC 179.

Before the final round, Aldo sat on his stool. Eyes shut, mouth open, gasping down labored breaths through his mouthpiece. Legendary Nova Uniao head coach, Andre Pederneiras, urged Aldo to “just worry about breathing.” His shoulders heaved with the weight of each breath, as the cut-man dragged a crimson rag across his face, wiping blood as it leaked from his nose. He nursed a wound on his swollen eye that had recently cracked open from a Mendes right hand.

Color commentator, Brian Stann, expressed worry over Aldo’s condition:

“We are not used to seeing this from the corner of the champ!”

In the opposite corner, Chad Mendes looked relatively fresh. A slight red tone on his cheeks and a small mark under his left eye belied the damage he had taken at Aldo’s hands just moments earlier. Mendes’ trainer, Duane Ludwig, felt no need to comfort his fighter, instead jumping right into tactical advice. And for good reason - the previous round was his strongest of the fight. He made his entry feints count and used his lead hand deftly, setting up a series of right hands on the trickling eye of Aldo.

Aldo had done the better work throughout, but the fight was close enough - and judges sufficiently unreliable - that either man could conceivably earn it in the last round.

The fifth round is where the cracks in Aldo’s incomparable composure tended to show. While near impossible to hit clean or take down at his best, Aldo had long struggled with his cardio at the end of five-round affairs. Fights with Mark Hominick and Ricardo Lamas ended with Aldo lying on his back, giving up the final frame. Neither of those men pushed him anywhere near the degree Mendes was. He could usually afford to drop the last round, but he lacked that luxury tonight.

The final five minutes represented the culmination of Mendes’ athletic career. One of the best fighters never to hold a title, Mendes had the misfortune of coming up in a division already ruled by Aldo. After suffering a first-round knockout in his first bid at Aldo’s title a mere two years prior, Mendes went on a tear. He made concrete improvements in his game - notably with Ludwig’s aid - and finished his next four opponents in devastating fashion.

Mendes was peaking. The challenge of Aldo’s throne pushed him to heights he had never reached before, and would ultimately never see again. His offense was as potent as ever, but his setups were now multifaceted, jabbing and feinting into his combinations, using crafty shifting footwork to cover distance. His counters were diverse and sharp, his defense unusually sound. Aldo couldn’t possibly prepare for this iteration of his challenger; it was a new Mendes.

The stools were removed and the men took their positions. Mendes let out a quiet “Woo!” and stayed active, anticipating the start of the round with some labored bouncing. Aldo looked distracted, fiddling with his eye wounds and checking back at his corner.

Mike Goldberg and Brian Stann pointed out that Mendes’ gutsy performance must have increased his confidence. Stann mentioned that the final round “could very well decide the winner." Mendes would never again get an opportunity as ripe for the taking as this, and he wasn’t about to waste it.

The round started fast, as Mendes tagged Aldo clean three times in the opening ten seconds. A jab, southpaw straight left, and a lead hook, all set up by shrewd feints. Mendes continued feinting to draw out counters and dull the champion’s reactions. When Aldo lashed out on the lead, Mendes smoothly pulled back, slipped, or blocked it. The wrestler with a right hand had become a defensive slickster.

After nearly a minute had passed, Mendes did the impossible. He feinted inside, drawing an Aldo counter, and sailed right into a double leg takedown, catching Aldo with his hips square. After a perfect entry, he ran his legs and launched Aldo off his feet.

Aldo was in familiar territory, on his back late in the fight. Only this time, he couldn’t afford to wait it out.

After Mendes had racked up a minute on top, Aldo found his opportunity. Warned for inactivity by referee, Marc Goddard, Mendes postured up and threw a knee, giving Aldo the necessary space to wall-walk back to his feet. As soon as he was up, Aldo exited the clinch by shoving Mendes halfway across the Octagon.

Two minutes had passed without any effective offense from Aldo, and he knew he had some catching up to do. Aldo began walking Mendes down with renewed vigor. He found an opening through Mendes’ guard after a couple ineffective leads, landing a clean lead uppercut and rear straight. As Mendes barreled backwards, he stepped in and delivered a piercing knee to the chest.

Far from having the intended effect, Mendes caught the knee and turned it into another takedown attempt. Faced with the prospect of spending the remainder of the round underneath his opponent, Aldo summoned his strength and acted. He stamped his caught leg down and pivoted with extreme prejudice, throwing Mendes out of position and landing him on his hands and knees, before picking up a loose quarter nelson and smushing the wrestler’s face into the nearby cage.

The pace and accumulation was visibly wearing on Aldo, yet he refused to coast. He pushed forward on unsteady legs, almost as if harnessing his intense fatigue as a weapon. His once beautiful mechanics were rapidly decaying, and his positioning in exchanges was all over the place. At one point a blocked body shot from Mendes sent Aldo wobbling back, and upon re-entry he narrowly avoided an uppercut with an almost unconscious spasmodic motion. A second later he pushed forward and rocked Mendes with a tight right hand, before whiffing a desperate shovel hook that seemed to signal fatigue finally sapping all motor control from his body.

Aldo was too tired to throw proper punches, too tired to bring his feet with him when he attacked, somehow too tired to stop walking down and beating up Chad Mendes. Mendes appeared the fresher man in terms of mechanics and body language, but now it was Aldo doing all the effective work.

They say that fatigue makes cowards of us all, but not Jose Aldo. No, it made Aldo determined.

With a minute left in the round, Mendes made one last attempt to take the fight to the ground. His entry was clean; he got in on Aldo’s hips in great position, with enough momentum to lift him off his feet. Aldo simply rode it out with a whizzer before standing up and shoving Mendes to the canvas using his face as a lever. The man with one of the tightest double legs in MMA was made to look utterly silly for thinking he could take Aldo down, like a child trying in vain to topple his father. Mendes had asked and been answered emphatically: wrestling was out, it was not going to work.

The rest of the round was elementary, with a few insignificant exchanges. At the end of the fight, both warriors raised their hands briefly, before quickly succumbing to fatigue. Aldo scaled the cage and sat atop it, gesturing to a roaring crowd. There was a general understanding that the fight belonged to Aldo, competitive as it was.

It would have been so easy for Aldo to fade. To do as he had in past fights and take the last round off. Mendes’ strong start gave him the perfect opportunity to fall back into a lull, but Aldo wouldn’t have it. He decided the round would be his. Nothing was going to stop him.

Ultimately the last round didn’t matter, as all three judges saw Aldo winning three of the previous four. But that final round, perhaps more than anything else in his career, provides the perfect glimpse into the kind of fighter Aldo was.

When I think of Jose Aldo, what immediately comes to mind is his masterful ability to control the flow of a fight. In a way rarely seen in MMA - a way more reminiscent of the smooth jazz of boxing legends than the metal-core/glam rock of MMA - Aldo would ride the ebbs and flows of the fight as it played out, gently nudging it along his preferred route. He wouldn’t contest what didn’t need contesting; if his opponent was content to stand outside his range and lose a low-volume snooze-fest, Aldo was happy to oblige.

But Aldo was always ready to take a firmer hand. He had preternatural knowledge of exactly where he was in a fight at all times - exactly how many rounds he was up, exactly what needed to be done to secure the next one. If Aldo didn’t care to win a round, he’d focus on keeping himself safe whilst taking an offensive rest, or chill out on the bottom, using his guard to mitigate damage. If Aldo decided a round needed to be won to bring his vision of the fight to fruition, there was no stopping him.

After being thoroughly dominated by Aldo and knocked out in the second round, Manvel Gamburyan commented on his incredible generalship:

England, they’re a very fast [soccer] team. When they play Brazil, somehow Brazil slows them down and makes them play their game. I don’t know how it happens, but it’s the same thing with Jose Aldo. Even if you want to fight fast, or anything like that, he makes you go on his pace. It’s magic, or it’s just that he’s gifted. I don’t know. (1)

It’s almost inevitable that a fighter with Aldo’s mentality of doing just enough to win would at some point find himself on the receiving end of a poor decision. MMA is such a chaotic sport - and the eyes of its officiators so often drawn to empty volume and activity - that being fastidious with one’s offense carries a significant risk. It speaks to Aldo’s mastery in his role of conductor that he never came particularly close to giving up a fight because he simply didn’t do enough (aside from a severely post-prime loss to Alexander Volkanovski, in which he seemed to lack the cardio to do enough).

Chad Mendes was, at that point, Aldo’s most fierce competitor. Arguably the most impressive win on his resume. And the greatest example of exactly what lengths Aldo would go to in order to do what needed to be done.

An All-Terrain Fighter

When pundits say a fighter can do everything, they’re usually speaking in very broad terms. “He can strike and grapple,” or “he can punch moving forwards and backwards.” It’s a phrase meant to signal breadth of skill without being taken completely literally.

Jose Aldo could do everything, and I mean that in an incredibly granular sense. Pick any constituent discipline of MMA - he wasn’t good at it, he was world-class. But even more than that, he could fight any fight required of him. Given the absurd variety of skills one must navigate to succeed in MMA, it’s often difficult to trust fighters to fight in a way they haven’t demonstrated aptitude toward before, even if their skills seem to suggest they should be capable (see Calvin Kattar becoming flustered when forced to pressure, despite otherwise possessing fantastic boxing and footwork). Aldo could enter a fight with a new weapon, or even a new style of fighting, and he wouldn’t only guarantee competence, but he’d prove a paragon of the style.

By nature, Aldo was a pocket operator. He thrived in extended exchanges, more comfortable making opponents miss in close than anyone else in the sport. His comfort zone was just at the edge of his opponent’s reach or slightly closer, where either man could step in and put together combinations. But he was amazing everywhere, capable of adjusting his game as needed. When he chose to play the out-fighter - maintaining a longer distance and maneuvering around the ring to avoid his opponent’s offense - he was shockingly proficient. When opponents refused to engage him in the pocket and forced him to advance, he pressured as well as anyone, cutting the cage with small, measured steps to maintain his positioning while slamming sweeping strikes into his opponents’ body and legs, herding them into longer combinations.

Comfort Under Fire

Aldo was a very fluid fighter. He had his preferences and areas of strengths, but on a broad strategic level, his game would take different forms depending on what the situation demanded. He would almost let opponents choose their own demise. Standing just outside of range, daring his opponents to act, Aldo would wait until they demanded something of him. In an era where most elite fighters aim to enforce their own strengths to deny their opponents a chance to work, Aldo was content to give his opponents space and time to work. He was also the best defensive fighter in the sport’s history, which meant that the brunt of his opponent’s work was futile.

Analyst and friend of The Fight Site, Phil Mackenzie, explains Aldo’s peculiar defensive temperament:

Jose Aldo takes a different approach. He’s a defensive wizard, one who doesn’t prioritize learning or responding to his opponent’s patterns. Instead, his focus is on not having to do any of that at all, or on avoiding it as much as he possibly can. This is enabled by his defensive fundamentals, the multiple layers of his footwork, his head movement, his hand parries.

This itself becomes the root of a different type of adaptability. Take, say, Floyd Mayweather as the case study for combat sports defense. Floyd is famous for being an adaptable fighter, but the core of it isn’t that he takes in a lot of information and computes it all.

Instead it’s that he’s able to see the enormous corpus of data that an opponent represents, and then consciously ignore the vast majority of it, or better yet, to dump it into a kind of mental box labelled “minimal processing, use if necessary.” He has an automatic, built-in response to almost everything which can be thrown at him…

The amount that Floyd has to consciously think about is relatively small and so, for him, adapting is relatively easy. The heavy lifting of the defense is performed almost without thought, based in tenets of distance, foot position and pure reflexes…

That’s boxing’s greatest defensive maestro. It’s something like what MMA’s greatest defensive fighter does. (2)

Aldo is incredibly fundamentally sound in terms of his positioning, footwork, and defense. These fundamentals allow him to play an atypical nullifying game. For most fighters, allowing opponents more opportunities to work simply risks getting hit more. But if you’re trying to hit Aldo, you’re likely missing. And if you’re missing Aldo, you’re likely getting countered. And if Aldo’s countering you, you’re probably going to stop trying to hit him so much. It’s in this way that Aldo paralyzes opponents into inactivity, slowing the pace to a crawl - not through fearsome power, but through impeccable fundamentals.

Almost always in perfect position to react to attacks, Aldo keeps his lead foot trained on his opponent’s center-line and uses small, precise adjustments of his lead foot to stifle their lateral movement. He’s renowned for his ability to take angles both offensively and defensively. When looking to create opportunities of attack, he’ll use a sharp jab to advance diagonally, creating a route for his right hand, or throw his lead hook with a pivot toward his opponent center-line.

His defensive footwork shines even brighter, as he possesses perhaps the finest pivots in MMA.

Aldo’s tight, graceful lateral movement makes him incredibly difficult to pressure or line up for an attack. When forced to the cage, most fighters will circle out in a wide arc and give opponents an opportunity to follow them, but Aldo can simply close distance and pivot straight back to the center of the cage. His pivots serve to defuse linear rushes by breaking the line of attack. Breaking the opponent’s charge is not only useful to defuse attacks, but also to bookend his counters by exiting at an angle, cleanly ending the exchange and preventing follow-up strikes.

Along with aiding his ringcraft, his pivots allow him to create dominant offensive angles in the pocket.

Aldo uses a non-commital jab to draw out a counter from Chad Mendes, but his left hook is smothered. He steps in with a hard combination, but Mendes parries the jab and deflects the straight. When they exchange again, Aldo turns his lead foot inward and pivots, giving him a dominant angle where he’s facing Mendes, while Mendes is facing away from him. Now Mendes is unable to smother Aldo’s offense by pressing forward and must turn to face him, giving Aldo a window to crack him with a clean hook.

When opponents were able to stand him in place long enough to exchange on their terms, they were forced to contend with Aldo’s layered defense. No fighter in MMA possesses as deep a defensive arsenal as Aldo in his prime. His head movement alone was enough to keep himself safe in deep exchanges, smoothly transferring his weight between hips, slipping to both sides, and rolling cleanly under punches only to put himself right back in position to slip once again. But he combined that head movement with a responsive high guard that he could adjust based on his opponent’s actions and a lovely repertoire of more situational defense, such as parrying or extending his arms to bar punches coming from the outside. He had such incredible composure that it was not unusual to see him close distance in response to a hook in order to smother it - a move relatively common in boxing, but rarely seen used with intention in the chaotic sport of MMA.

Skip to 12:29 for a sample of Aldo’s masterful defense (and keep in mind that the entire clip was taken from only a single round of his work)

Graceful Savagery

Aldo’s primary tool in limiting his opponent’s options was his counter-punching. He was incredibly hard to hit clean on the lead and incredibly deft at making opponents pay for their attempts. Issues with his punching form prevented him from being the type of counter-puncher that regularly finishes his man clean, but he packed enough power to drain the aggression out of his opponents after they had tasted a few.

While Aldo possessed a versatile array of counter-punches, he did much of his best work countering the jab. As his tight positioning, footwork, and defense were likely to win him exchanges in the pocket, taking away the jab became a crucial part of his strategy. He would often set up a single step beyond his opponent’s range, forcing them to come forward in order to reach him. The highest percentage tactic to close the distance is simply advancing behind a jab, but Aldo was always waiting on it, poised to counter. When his opponents found themselves out-gunned on the inside and foiled in their attempts to put themselves in position to attack, it was common for them to slow down, consenting to a fight on Aldo’s terms.

For most of his career, Aldo used a sharp kicking game to score at long range while either tempting his opponents to step onto his counters, or walking them down to land his punches. The most consistent tool in this arsenal was his outside leg kick. Aldo’s leg kicks were famous for their brutality, but he sacrificed nothing in science to achieve bone-crushing impact. He could reliably land them on the lead or the counter - set up by timing his opponent’s forward steps, or sticking them on the end of punches.

Aldo did not discriminate in terms of targets. He made a habit of working the body, a tactic which nearly every MMA fighter could stand to do more. He was never the most consistent body puncher - he didn’t build body work into most of his combos or use it to create double attacks with his head strikes more than occasionally. But what he lacked in consistency, he made up for in determination and finesse.

His body shots served two primary purposes. The first was a simple power strike. He would draw his man’s hands up with a feint or a throwaway punch upstairs, then smash the body with brutal hooks.

While Aldo’s willingness to throw leg kicks fell off late in his career, likely a result of injuries as well as frequent fights against wrestlers, he often relied on his body shots to set up his leg kicks. In a classic Dutch combination, a punch or two to the head is used to draw the hands high, then a body hook shifts the opponent’s weight onto their lead leg and puts the attacker in position to throw a leg kick. While Aldo’s striking style was often described as “Muay Thai,” his kicking game bore far more resemblance to the Dutch kickboxing style.

A Brick Wall

So far we’ve only discussed Aldo’s world-class striking. The answer to such a skillset would seem obvious: remove him from his domain of comfort and take him to the ground. Unfortunately for Aldo’s contemporaries, it turns out that trying to take him down was the easiest way to ensure certain defeat. Aldo simply did not believe in wrestling, and he proved time and time again that the delusion lied on the side of the wrestlers.

Aldo had the unique experience of being a striker by trade who was essentially impervious to wrestling. He wasn’t completely invulnerable, and he was taken down now and then, but only on rare occasion, and never for long (unless he had already won the fight and was content to burn out the clock). Wrestling against Aldo was more useful for setting up strikes than it was for actually taking and holding him down. Nova Uniao was instrumental in elevating takedown defense for strikers in MMA, and Aldo was their standout representative.

While Aldo’s defensive wrestling is deserving of a more in-depth study, there are two concepts that stand out in importance - his footwork and grip-fighting.

The same striking footwork that gave opponents trouble in exchanges made taking Aldo down a herculean task. His impeccable positioning meant that opponents were typically forced to initiate their shot from a weak angle, but once they made penetration, he would pivot out with extreme prejudice while whizzering and pushing the head down or framing it away.

In order to hit a clean double leg, you need to be facing your opponent’s hips, ideally with them square in front of you. Aldo’s pivot would rip his rear hip away from their grasp and view, eliminating all hope of finishing the double. Often opponents would be thrown off both hips with just the pivot, but if they still clung to a leg, he’d simply push the head and limp-leg out.

Pundits often refer to Aldo’s pivoting style of takedown defense as “feeding the single,” but it’s somewhat of a misnomer as applied to Aldo. Feeding the single is when a fighter closes off the double leg and allows his opponent to take an easier to defend single leg, with the intention of slowing the takedown’s finish, usually by hopping back to the cage and breaking grips. Aldo did not give opponents his leg, he violently ripped it out from under them and with it, their positioning. The only thing he fed was faces straight into the mat.

When Aldo found himself pressed against the cage, he relied on his stellar ability to break grips. The concept is simple enough: in order to make a strong attack against your hips, I need to lock my hands together, whether around a limb or a body. By controlling the hands and preventing that lock, one can deny a wrestler leverage to stage that takedown. While grip-fighting is an important part of late-stage defensive wrestling in collegiate and Olympic wrestling, it takes on new importance in MMA.

If your opponent drives you back on a wrestling mat, you’ll go out of bounds and reset. If your opponent drives you back in an MMA cage or ring, you’ll hit a wall. This is great for wrestlers, as many traditional means of takedown defense become obsolete or difficult when forced against an un-moving surface. Creating distance is out, as there’s nowhere to go. Frames can be worked around more easily, and lateral movement becomes near impossible. A wrestler can hold his opponent on the cage while he takes time to put himself in a strong position to finish his takedown. Grip-fighting becomes absolutely crucial when defending takedowns against the cage, as it’s often the only reliable way to disrupt the wrestler’s positioning.

Cage-adjacent takedowns can often trip up even the most experienced wrestlers who are not used to the dynamic (such as Olympic silver medalist, Yoel Romero), but Aldo is the best example of how a striker can use the cage to his advantage by aggressively fighting grips. Too often we see strikers concede takedowns because they forget themselves for a moment, either being slow to attack the grip or using their free hand to throw light punches, but Aldo’s urgency and discipline was astounding. He treated hands locked around his leg or waist the way most fighters treat a locked-in rear naked choke.

As soon as his opponent was in on his hips, his hand would immediately control their bicep or wrist, attempting to pry the grip off. If they attacked a double leg, he would pry a wrist off his waist and force them to take a single. When they had only a single leg under control, Aldo would patiently fight the grip, waiting for his opponent to change directions and take him off the cage to finish the takedown, at which point he would aggressively push the head down and limp-leg out.

Cat-like recovery skills propped up his takedown defense. When Aldo did find himself on the bottom, he wouldn’t rest until he stood back up. He fought tooth and nail, using the brief window of opportunity when the opponent had finished their takedown but not yet solidified control to elevate his hips and scramble up. He was a more than competent offensive wrestler as well, capable of taking all but the best wrestlers down to slow the pace and give opponents something else to worry about. Although Aldo rarely showed off his top game, he was a guard-passing maestro, capable of slicing through guards with seemingly minimal effort.

There’s far more to Aldo’s legendary defensive wrestling and grappling than I can cover here, so check out this more in-depth breakdown by my colleague, Ed Gallo.

From Favela Kid to Breakout Star

Aldo was born in Manaus, Amazonas to a bricklayer who struggled to support him. His first martial art was capoeira, before financial difficulties forced him to abandon it. It was then that Brazilian Jiu Jitsu found him - not for its efficacy, but its accessibility. Trainer Marcio Pontes saw something in Aldo and took the future champion under his wing, providing him a free gi and affordable training.

Aldo was soon hooked. He dedicated himself to his training, setting his sights on Rio de Janeiro, which seemed like a pipe dream for a poor kid from Manaus.

"I started training hard to one day be able to go to Rio de Janeiro and win a tournament there," says Aldo, who looked up to other successful Manauaras like Wallid Ismail and Saulo Ribeiro in jiu-jitsu magazines. "That was my focus. I trained three times a day, because I knew that could give me a better future." (3)

He eventually made it to Rio, first under a government-sponsored program to compete in the 2001 CBJJ World Championships, and later as a resident. When his team arrived in Rio, they were all tired and wanting rest, but he insisted on going down to the beach to see the ocean. MMAFighting’s Guilherme Cruz writes:

Every step in that direction gave Aldo butterflies. There was no such thing as cell phones and cameras for a poor kid like Aldo. All he had was his eyes, and he made sure to enjoy every second of that adventure.

He was gone for a couple hours until he finally walked back to Barata Ribeiro Street — picking up a few little shells and sticking them in his pocket along the way, so he could prove to his mother that he really made it to the Copacabana beach. (3)

A few months after the World Championships, where he took bronze in his weight class, Aldo finally moved to Rio de Janeiro on a permanent basis to train with Andre Pederneiras at Nova Uniao. Arriving at the gym with little more than the clothes on his back and nowhere else to go, Aldo would spend his time alternately training and sleeping on the mats. Nova Uniao was known primarily for its strong BJJ team at the time, but Aldo would later help elevate it to legendary status within MMA.

Although Aldo had found the team and the coach that would take him to international stardom, it was anything but smooth sailing initially. When Pederneiras relocated his gym to Flamengo, Aldo was no longer able to sleep on the mats. Nova Uniao teammate, Hacran Dias, provided him refuge; a small house in the Santo Amaro favela with Dias and his mother, Julia. Living in the favela, Aldo was surrounded by crushing poverty and an abundance of crime. One can only imagine how difficult it is for a favela kid to avoid the rampant crime outside his front door, but Aldo credits Dias and his family with keeping him focused: “They kept telling me that wasn't good, and that's why I stayed away from it."

"I thank Hacran and aunt Julia for the help. I love them," says Aldo, who stayed with the Dias family for seven months. "This is why I say Nova Uniao is not a team, it's a family. I always had someone to count on when I needed." (3)

After quietly amassing a 10-1 record in his first three years of MMA competition, Aldo got his first big break. A fight in the WEC against the veteran Alexandre Franca "Pequeno" Nogueira. Aldo had previously struggled to find fights due to his weight class. At the time, the UFC lacked a Featherweight division, and opportunities on the regional circuits were scarce. The WEC was the premier organization for weight classes under 150lbs. Proving himself here might be his only ticket to opportunity.

Nogueira was a former Shooto champ who dominated in the organization for years. While his dominance had faded by this point, he captured the Shooto 143lbs title in his second pro fight and won 10 more in Shooto between the years of 1999 and 2005, avenging his only two losses in immediate rematches. Journalist Shaun Al-Shatti had this to say about the fight:

Take it back to 2008. Seven years before the entire city of Dublin turns on him, the greatest featherweight of all-time arrives stateside as a sidebar to a reclamation project. Lion’s food for an aging lion. Alexandre Franca Nogueira, on the other hand, is the real story. He is Jose Aldo before there is Jose Aldo — an overpowering Brazilian who ruled over Shooto for the better part of a decade, gorging on a steady diet of overmatched Japanese fighters. Nogueira’s reign is over by the time he lands on the deep undercard of this WEC show, but even then ‘Pequeno’ is still a name, and names need to feast.

They sacrifice the poor kid from the favelas. (1)

It was a sacrifice, but not the one they expected. The commentators admitted their lack of familiarity with Aldo, but Frank Mir was certain that he was “no slouch” on the ground due to his Pederneiras black belt.

He wasn’t an up-and-coming challenger campaigning for fame and glory so much as a starving man fighting for his next meal

Aldo looked a weight class bigger than Pequeno and as fast as a Flyweight. He walked the veteran down, feeding him a steady diet of lead hooks and straight rights. Pequeno had nothing for Aldo in any phase of the fight. He was quickly shocked into inactivity by Aldo’s power and effortlessly shrugged off every time he attempted a takedown. Halfway through the second round, Pequeno fell to his back after a failed takedown and Aldo passed his guard like a hot knife through butter before finishing him with strikes.

Aldo had arrived. They knew his name now and they would not soon forget.

From that point onward, the Nova Uniao prospect became a one-man wrecking crew dismantling the WEC’s Featherweight division. His next three opponents were all finished in devastating fashion. Among them, only Jonathan Brookins made it out of the first round, and he suffered all the more for it. Aldo walked Brookins down, smashing his leg with kicks and pelting him with counters when he attempted to stop the bleeding.

Early Aldo had the type of style that instills hesitance in managers. Accepting a fight with Aldo meant not only likely defeat for your fighter, but it carried the promise of pain and injury in every part of his body. Aldo was a wild man who threw every strike as if it was his last opportunity to irreparably damage a limb or an internal organ. There was a primal desperation within him. He wasn’t an up-and-coming challenger campaigning for fame and glory so much as a starving man fighting for his next meal. He beat his opponents like they were piñatas containing the path to a stable life.

These fights also introduced new elements of Aldo’s skillset. While it may be easy to question Pequeno’s tactic of retreating, shooting from too far away, and largely hoping Aldo would stop hitting him, trying to hit Aldo back proved a tremendously silly thing to do. The Brazilian dynamo was as savage on the counter as he was on the lead, as Brookins discovered when he ran face-first into an Aldo right hand that ended their fight. His leg kicks were as versatile as they were devastating. Whether hidden behind dutch-style combos or used to counter his opponent’s forward movement, he found opportunities to smash them in consistently regardless of his opponent’s habits. You could shell up and eat punches and kicks, or you could move forward and eat them harder.

There was a fascinating duality to Aldo’s game. His wild flurries and fits of rage sat atop a rock-solid and ever-strengthening fundamental base. One moment he’d deliver swings that wouldn’t look out of place in a vertically-filmed video featuring several undercover Brazilian cops, and the next, a gorgeous slip, pivot, and counter. The rampaging destroyer moved his feet like a graceful boxer, exhibiting meticulous awareness of his positioning and beautiful lateral movement. He was still young and raw, but there were signs of the master technician he would later become.

After nearly a full calendar year spent in the WEC and four finishes in as many fights, Aldo was set to move up in the division. His next fight was a title eliminator against Cub Swanson, a future mainstay of the UFC’s Featherweight division. Swanson was a bright prospect, with a 13-2 record, coming off a fight of the night win over Shooto and HERO’s standout, Hiroyuki Takaya. The winner would be granted an immediate shot at the WEC’s Featherweight belt.

The fight was over quicker than it began. Aldo rushed toward Swanson immediately and Swanson changed levels to meet him with a body shot. Aldo leaped into the air and kneed him twice. Swanson collapsed on the canvas, facing the ground with his hands covering his head. Aldo stood over him and punched him into the fetal position. The ref stopped the fight eight seconds in. The quickest win of Aldo’s career came via flying knee - in one motion he had kneed Swanson two times, each knee opening up a separate cut on his face.

While Aldo made mincemeat of the lower rungs in the Featherweight ladder, another battle took place at the upper echelon. For most of the division’s history, the Featherweight belt belonged to Urijah Faber, the “California Kid” and the golden boy of the lighter divisions. Faber captured the title in 2006, three years prior, against Cole Escovedo and defended it five times.

At WEC 36, the same night Aldo destroyed Brookins in his second promotional bout, Faber dropped the title to Mike Thomas Brown. Faber attempted a risky backwards elbow using the momentum of the cage to launch himself forward, straight into Brown’s fist. After a first round TKO victory over the famed California wrestler, Brown quickly finished Leonard Garcia before his second meeting with Faber. This time, Brown would grind Faber out in a strange fight in which Faber broke both hands and resorted to elbowing and slapping in the later rounds.

Aldo’s eight-second finish of Cub Swanson put him on a direct collision course with Featherweight champion, Mike Brown, at WEC 44.

The Champ is Here

Brown was on a 10-fight win streak coming into his fight with Aldo, holding victories over elite fighters such as Urijah Faber, Jeff Curran, and the aging but still extremely talented Yves Edwards.

While the competition Aldo faced on his way to the title consisted largely of over-matched fodder who were no match for him athletically, Brown presented a new threat. Brown was an excellent wrestler and clinch fighter who could test Aldo’s takedown defense and positional awareness in a way nobody ever had.

Brown wasn’t an incredibly skilled boxer, but he possessed a powerful right hand and was crafty about setting it up, using jabs and leaping lead hooks to carry himself into the pocket. His skills worked in tandem with each other, as punching combinations lead him into the clinch, where he would look to do damage with dirty boxing while creating openings for takedowns. Most importantly, Brown was a capable athlete, large and strong for his division. He was expected to have less trouble matching Aldo’s physicality than previous opponents.

The betting public expected a close fight. The odds closed near even, with Aldo as a very slight underdog. It was clear that Brown couldn’t match Aldo’s skill in a striking match, but he had paths to victory. It would come as a surprise to no one if Brown retained his title.

Aldo opened the fight slowly, observing Brown and reading his reactions. As the fight went on, he began to tee off with kicks, knees, and punching combinations. Browns’s vaunted wrestling was useless against the challenger. Aldo would preempt Brown’s clinch entries with an underhook and circle out of danger.

When Brown pressed him to the cage and made for his legs, Aldo simply widened his base and pried Brown’s grip off. As any good wrestler would when plan A fails, Brown attempted to chain, moving from the double leg to a body-lock takedown, but he was unable to bypass Aldo’s incredibly strong and dexterous hips. A slew of lead-leg knees and switch kicks from Aldo kept the champion hesitant to change levels into his takedowns, as every level change carried the risk of running into the knee.

It’s his hips. He’s got great balance and great hips. That’s the term we use in wrestling. The ability to keep your hips squared to the mat and not go over, you know? He’s got it. (1)

- Mike Brown

A minute into the second round, Brown leaped in with a missed lead hook and went down in what was half unforced error and half Aldo takedown. Aldo immediately pounced, took the champion’s back, and finished him with strikes for a TKO win.

Aside from a few minutes of ineffective cage control, there was nothing in Brown’s performance to distinguish him from the over-matched opposition Aldo decimated on his rise to the title. The challenger looked untouchable against his greatest challenge yet.

When Brown was standing in the pocket or backing up, Aldo was in front of him pelting him with kicks, punches, and knees. When he went on the offensive himself, Aldo was a ghost, quietly slipping out of range. His jabs that usually carried him into range for the right hand were parried with no issue. When the wrestler started leading with right hands, unable to close distance with the jab, Aldo would simply raise his left to block them cleanly. At one point, Brown timed a perfect cross-counter, slipping inside an Aldo jab and throwing an overhand; an excellent setup for a hurting punch, but Aldo just lifted the jabbing arm and watched it bounce harmlessly off his forearm.

Aldo beat Mike Brown so easily and so thoroughly that it caused a generation of MMA fans to forget how important the win was.

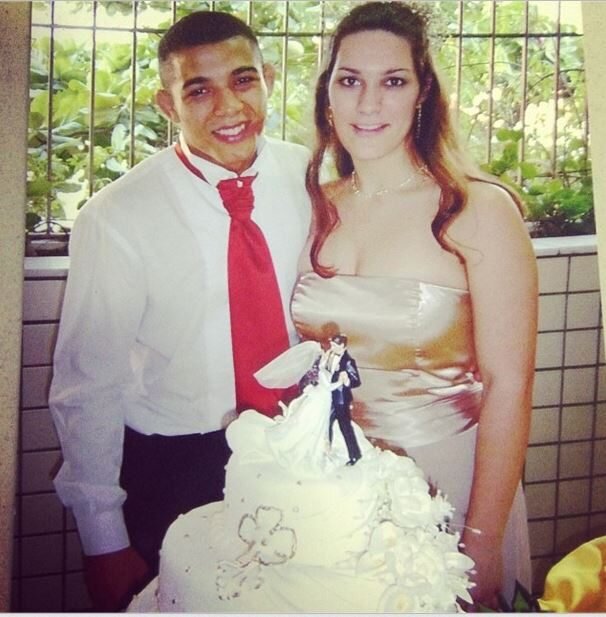

With a dominant win over Brown, Aldo had finally made it. A few short years ago he was wracked with uncertainty, wondering whether he’d be able to find fights consistently enough to sustain himself. Now he was the champion in the premiere organization for his weight class. More important than the belt, however, was the security it represented for Aldo and his wife, Vivianne Pereira.

"Our lives changed when he went to WEC," says Pereira, who couldn't stop crying after watching her husband win the WEC title a couple years after they got married. "We were finally able to fulfill a dream and buy our own apartment. (3)

Shortly after Aldo captured the WEC Featherweight championship, Faber thrust himself back into title contention with a win over Raphael Assunção. A fight between Aldo and the former champion was booked for WEC 48.

It soon became clear that what Aldo did to Mike Brown was a mercy. Brown was beaten up and finished within seven minutes, but Faber had no such luck. Aldo tortured Faber for five long, painful rounds, systematically breaking down every part of his body.

Lead hooks and intercepting knees tore apart Faber’s midsection, puncturing his gas tank and forcing him to the floor several times. It was his legs that sustained the most damage, however. Faber’s heavily bladed stance made him a perfect mark for Aldo’s leg kicks. Once his lead leg had been thrashed so thoroughly he could barely stand on it, Faber began overcompensating by lifting his leg high to check and alternately switching to southpaw. Both these moves made his rear leg a prime target for the kicks as well.

Faber compared Aldo’s leg kicks to being hit in the thigh with a baseball bat:

Looking back, I remember actively having to hobble after him at one point. Like actually having to limp. I was just… for me it was like, alright, how am I going to hit this guy? So I just switched stances and kept trying to hit him with the right hand. Even when he kicked me to the ground, I can’t remember exactly how I went down, but I couldn’t bend my leg at all. Like, I really [couldn’t] use my leg on the ground either. I felt like I was going to pass out from the pain by the time I did the post-fight interview.

I’ve never been hit with a bat. But I think [that experience] would be kind of like how it feels to get hit with a bat. Like somebody aiming at you with a bat. That’s the best way to describe it. Over and over and over. (1)

Once again, Aldo had dominated a world-class fighter while hardly being touched himself. By the last few rounds, Faber’s base was far too compromised to offer any effective offense, but even early in the fight, his linear attacks were largely nullified by Aldo’s lateral movement. Aldo displayed the defensive acumen that frustrated Brown, but this time he was more active in his head movement, chaining slips, bobs, and weaves together. Faber wasn’t able to push exchanges far enough to really test Aldo’s defense, sticking mostly to pot-shots and linear blitzes, but it held up swimmingly nonetheless.

The next name on Aldo’s hit list was Manvel Gamburyan, whose recent knockout of Mike Brown had earned him a title shot. Aldo took the first round to feel Gamburyan out, before catching the Armenian Judoka with a series of uppercuts that sent him to the ground early in the second. Gamburyan was a step down from Aldo’s recent competition, but Aldo finished him in style.

The UFC’s parent company, Zuffa, had owned the WEC since 2006. Shortly after Aldo’s title defense over Gamburyan, Dana White announced plans to merge both promotions together. The lighter weight classes would finally reach the biggest stage in the sport. Aldo was promoted to UFC Featherweight champion and set to fight Mark Hominick in his promotional debut. Joining the UFC meant that Aldo would now have access to a wider pool of competition, as well as increased visibility and pay.

King of Rio

Hominick was Aldo’s toughest test since his early loss to Luciano Azevedo. One of the most skilled offensive boxers in MMA at the time, Hominick was known for his lovely, complex combination work. In an era where most combinations were limited to flurries or alternating right and left hands, Hominick was doubling up on his punches, mixing body and head work, and building rhythm breaks into his combos. Hominick had a very strong all-around game as well, with excellent counter-punching and strong submission skills on the ground. Hominick’s defensive skills were notably weaker than his offense, but he was capable defensively and skilled at disguising his entries with feints.

While he didn’t exactly make the champion taste his own blood, Hominick made Aldo work for his victory nonetheless. The Canadian boxer feinted around at range, picking away with a jab to create openings. When he found those openings, he was prepared to engage Aldo in pocket exchanges. It was the first time we saw Aldo fight someone who could box with him, and he passed the test with flying colors.

Often Aldo would slip Hominick’s initial shot and immediately close the exchange with a sharp counter. But when Hominick was able to force him deeper into exchanges, we were finally treated to a part of Aldo’s skillset that nobody else had forced him to show. He had layers to his pocket defense.

Many of fighters can slip a single punch thrown from the edge of boxing range. A few can comfortably slip two punches in the pocket without compromising their positioning. Although the form of his head movement wasn’t perfect - he leaned slightly at the waist instead of engaging the hips fully - there was seemingly no end to the defensive layers Aldo possessed. He could parry and slip Hominick’s jab all day, but he was still there to slip outside the subsequent right hand and immediately roll under the left hook. If the Faber fight demonstrated the incredible difficulty of closing distance on Aldo, Hominick showed that Aldo didn’t need distance to make you miss.

It’s a credit to Hominick’s skill that Aldo felt it necessary to employ a fully-rounded game against him. Aldo had mostly played the role of the pure striker in his WEC tenure, sprawl-and-brawling his way to the title. Aldo outboxed the standout boxer and punted him with leg kicks, but he also took him down several times, using double legs to secure rounds and instill hesitance into Hominick on the feet.

Although Hominick lost each of the first four rounds on the judges scorecards, he ended the fight on top of Aldo, taking the fifth round with ground and pound. Hominick had been stunned with an uppercut and attempted a desperation shot. Aldo went for a guillotine and ended up on his back. Though fatigue certainly played a role, the guillotine-to-defend-takedown is so out of character for Aldo that it seemed to represent a concession of the round, secure in the knowledge that he had already won.

It wasn’t a war. Aldo won a fight that wasn’t especially close, beating a softball-sized hematoma onto Hominick’s head along the way. Hominick failed to push Aldo to his absolute limit, but he gave us a glimpse of how Aldo handles adversity. When forced into deeper exchanges with a man who belongs there with him, Aldo excels.

Aldo’s next victim was perennial bridesmaid, Kenny Florian. Florian was a jack-of-all trades who could compete in any phase or range. Although he possessed competent boxing, his real strengths were found in his kicks and top game. Unfortunately, Florian lacked the wrestling to take the fight to the ground against opponents with great takedown defense. Nevertheless, since his debut at Lightweight only three years into his MMA career, Florian had only lost in Championship fights or number-one contender’s fights.

After a slow first round that Florian won on volume and cage-control, Aldo swept the fight. It was a low volume affair, with Aldo picking Florian off at range and Florian attempting to press the champion to the cage in search of takedowns. Aldo stymied Florian’s wrestling with ease. Whenever he came close to finding himself underneath Florian, he would immediately scramble up. On several occasions Florian was forced to his back and Aldo once again made short work of his guard, quickly passing to mount.

Though the former Lightweight possessed a distinct size advantage, it was no match for the champion’s incredible athleticism and takedown defense. Florian avoided the beatdown that the last several opponents received, but he was outclassed nonetheless.

Aldo returned to action only three months after beating Florian for his first fight with Chad Mendes. The fight was booked in the main event slot at UFC 142. It would be Aldo’s first time in the main event of a UFC card.

At this point, Mendes was a powerful right hand away from being a pure wrestler. He had developed none of the craft in his striking that he’d later become known for. Only four years into his professional MMA career and coming off a string of wrestling-based wins over talent that was solid but not elite, Mendes was simply not ready for Aldo.

The fight was not terribly significant from a competition standpoint, but the circumstances surrounding it were important. UFC 142 took place on Aldo’s home turf, in Rio de Janeiro. His fight with Mendes marked the first time Aldo had fought in Rio since his early days on the Brazilian regional circuit. At one point in his life, Aldo was ecstatic at the mere opportunity to compete in Rio. Now he was the main attraction on the biggest stage in the sport.

When asked about his opponent in the lead-up to the fight, Aldo promised violence:

After I knock him out at home, the fans will go crazy with happiness. (4)

Even Aldo may have been surprised at the prescience of his words.

By now, it was no secret what Aldo does to pure wrestlers - he chews them up and spits them out. Mendes was no different. The fight started slowly as both men traded leg kicks. Mendes looked to time reactive takedowns as Aldo stepped in, dropping back into a southpaw stance and shooting doubles. Aldo would gracefully pivot out on Mendes’ entry, forcing him to settle for a single leg, before pushing his head away to break his posture and limp-legging out.

Every eye in the building was on Aldo as the crowd cheered, chanted, and raved in his favor.

Late in the round, Mendes finally found a route onto Aldo’s hips as the Champion rattled off a combo capped with a committed leg kick. As Mendes turned the corner to finish his takedown, Aldo went belly-down and based out on his hands and knees. He stood up immediately, but Mendes had his back. After a few failed mat returns (one of which was prevented by a timely but illegal fence-grab from Aldo), Aldo broke the grip on Mendes’ body-lock, freeing himself from the control. Mendes looked to change levels into another takedown as Aldo turned out, but Aldo drove a knee straight through his chin as he ducked. Mendes was done, Aldo needed only a few punches on the ground to finish him off.

The fight itself was elementary, but what happened afterwards was a spectacle. After knocking Mendes out in minutes, Aldo immediately sprinted out of the cage and into the Rio de Janeiro crowd before security could restrain him.

The former favela kid was swarmed by a mob of adoring fans. Every eye in the building was on Aldo as the crowd cheered, chanted, and raved in his favor. They raised his hands in victory; they hoisted him atop their shoulders.

A little more than a decade ago, Aldo marveled at the act of merely reaching Copacabana beach and basking in the sight of the Rio de Janeiro ocean. Now he was surfing atop an ocean of adoring fans in the city of his boyhood dreams. Aldo was determined to bathe in the energy of the Rio crowd as long as possible, resisting the security personnel’s attempts to corral him back into the cage.

Although he had not risen to international superstardom, his popularity subsequently skyrocketed among the Brazilian fanbase.

"Few people knew him before he went to the UFC," Pereira recalls. "In Brazil, nobody knew what MMA was, only hardcore fans knew about MMA and the UFC. We took the subway and nobody knew who he was. It has changed a lot since the first UFC event in Rio, but he continues to take the subway every day." (3)

Every step in Aldo’s rise must have felt like a fever dream to him, but his ascent never slowed. His run as WEC contender and champ would have been a worthy peak, but it was already eclipsed by the grandeur of his short UFC career.

Aldo, however, was just getting started.

Aldo vs. Edgar

Aldo had reached the peak of the sport. As a now-dominant UFC champ, he had finally acquired all the stability, glory, and guaranteed pay of which he’d always dreamed. While he was already among the most accomplished fighters in the sport, making the top five in most pound-for-pound lists, he still lacked a signature, career-defining win.

The generation of Featherweight greats preceding Aldo had been mercilessly snuffed out, but his record lacked a modern great. As MMA is such a young sport, talent tends to make massive tactical, technical, and strategic leaps in just a few short years. This rapid pace of evolution means that changes are constantly made to the metagame, and fighters are increasingly learning how to take advantage of it as the sport ages.

After beating Mendes for the first time, Aldo would sit out a year until February 2013, when he met that first modern great.

Frankie Edgar was a new type of fighter. The sort of fighter that was in short supply 10 years ago, but is becoming increasingly common. While previous opponents like Faber and Brown could strike well and wrestle better, Edgar was a fighter in the Georges St-Pierre mold. He was never simply striking or wrestling, he was always actively engaged in every phase.

Edgar made his hay in transitions. He was one of the best wrestlers and grapplers the sport had ever seen, as well as a capable striker, but it was the synergy between those skillsets that made his game so unique. Edgar’s rapid lateral movement and active entry feints allowed him to set up shots and draw out counters to provide a route onto his opponent’s hips. He was also a master of disguising his takedowns, utilizing various attacks that mimicked the preliminary motion of his takedowns to prevent opponents from reading his intentions. Constant level changes, dipping jabs, and body shots hid his penetration steps, while jabs to the head hid his famed knee pick.

For a more in-depth look at Edgar’s excellent wrestling, check out another article by my colleague, Ed Gallo.

The synergy also operated in reverse, as Edgar’s wrestling opened up his striking. On its own, Edgar’s striking was sharp and crafty, but flawed. He made excellent use of feints and his boxing on the inside was always tight, but despite all his constant circling at range, he tended to enter on a straight line. By hiding punches and kicks behind his takedowns, however, his attacks became much less predictable. It wasn’t uncommon to see Edgar use strikes to open up a takedown entry, before dropping the leg and using the opening to hit. After multiple sequences like these, his opponents would be left unsure whether to focus on grappling or striking, and as a result more vulnerable to each.

The best example of Edgar’s skill in transitions was his trilogy with Gray Maynard. Maynard won their first fight soundly, using tighter striking and wrestling to control a very raw, inexperienced version of Edgar. Their second fight resulted in a draw, as Edgar struggled heavily with Maynard’s striking and takedown defense early, before mounting a comeback late. In their third and final fight, Edgar still struggled intensely in each phase, but he found the area he possessed an advantage - in transition. Late in the fourth round, Edgar shot onto Maynard’s hips, forcing Maynard to expose his flank in defending the takedown. Before Maynard had finished standing up - while he was still focused on grappling - Edgar slammed a right hand into his face and swarmed to finish the fight.

The contest between Aldo and Edgar was essentially a superfight. Edgar had won the Lightweight (155lbs) Championship in 2010 and defended it against B.J. Penn and Gray Maynard. While he subsequently lost the belt to Benson Henderson, he was gifted an immediate rematch at Henderson’s title. Although the result of the first Henderson fight was a clear loss for Edgar, their second fight is widely considered an undeserved win for Henderson, as fans and media overwhelmingly saw Edgar doing the better work. Edgar, widely considered the rightful Lightweight champion, was moving down to face the dominant Featherweight champion in Jose Aldo.

We knew Aldo ate wrestlers for breakfast, but Frankie Edgar was no simple wrestler. Not only was he more skilled in that area than most previous opponents, possessing a much greater ability to enter into his takedowns and a greater depth of chain wrestling, but his striking added a new dimension. If Aldo prioritized defending the takedown, it would leave him open to Edgar’s strikes. The more strikes he ate while focusing on the takedown, the more it would open him back up to Edgar’s wrestling. It was a challenge unlike any Aldo had faced in his career.

Aldo seemed to reinvent himself for Edgar. Gone was the wild swinging he displayed in previous fights, replaced with careful, measured boxing. He knew Edgar’s meticulous footwork would carry him away from wide swings, or else his tight boxing would allow him to punch inside them. Instead, Aldo replaced brawling with jabbing.

Up to the Edgar fight, Aldo’s jab had been fairly one-note and used mostly to set up his power shots. Aldo somehow overhauled that weapon completely within the year since his last fight, as he displayed one of the better jabs in MMA against Edgar. He needled Edgar with jabs from long range, scoring where the shorter man could not reach him. When Edgar attempted to rush into the pocket, he found himself intercepted by stiff jabs, or distracted by jabs while Aldo pivoted or circled out. Aldo would also use the jab to enforce his distance after exchanges, pelting Edgar with a kick or power shot before jabbing back outside.

Along with using the jab as a tool to dissuade Edgar from entering, Aldo used it to set up more powerful offense. A few times he took the lead and jabbed into his right hand, but he was mostly content to sit back and counter Edgar’s rushes. The jab proved pivotal in encouraging Edgar to throw the punches Aldo wanted to counter. He would flick out a light jab to prompt an Edgar charge, before taking a hop-step back and landing a lead hook or straight right over Edgar’s jab.

Edgar was largely kept on the outside, struggling to find entries. Before the fight, Aldo was seen as the matchup’s power-striker, while Edgar was the finesse guy. If the challenger won, it would be through dancing around the more powerful champion and playing stick-and-move while draining his cardio. That didn’t happen, however, as the powerful Aldo gave the would-be slickster a lesson on boxing and footwork.

For the first two rounds, Edgar couldn’t even maneuver himself into position to hit Aldo, let alone land consistently. His active lateral movement was utterly fruitless, as he failed to achieve dominant angles of attack. Any time Edgar circled in a wide arc, Aldo would simply adjust his lead foot to face him, leaving him in perfect position to counter when Edgar attacked. When Edgar came in on diagonals, Aldo would pivot with him and crack him with a check hook or circle out and counter with the right hand as he turned.

Aldo fought somewhat against type, playing the matador and leading Edgar around the Octagon. In his previous fights, Aldo preferred to face off in the pocket or just at its edge. He was often forced to pressure a retreating opponent in order to maintain his preferred distance. Against Edgar, however, Aldo largely kept to the outside. It was his first time playing the out-fighter and he did it better than almost anyone in MMA. His distance management was impeccable as always, but he was employing new tactics like feinting direction changes to escape the cage and circling out or countering on diagonals. His incredible lateral movement aided him greatly, as he danced around the cage like a ballerina, leading Edgar into powerful counters and frustrating his attacks.

The transitions that were so promising for Edgar barely occurred at all. At one point he caught an Aldo kick and hit a knee tap while landing a clean right, but Aldo stood up immediately. For the most part, Aldo entered and exited exchanges on his terms. Edgar’s knee pick and shot takedowns were foiled without any opportunity for a follow-up. Aldo would frame Edgar’s head away with a collar tie while pivoting to kill his positioning, preventing him from chaining or striking off the failed takedown. Edgar only got Aldo to the ground twice, and each time Aldo stood up within seconds.

Although Aldo dominated the first half of the fight, the momentum changed in the later rounds. Aldo had shown cardio issues in the past, while Edgar was famous for his high pace and tireless cardio. Aldo was able to slow the fight down and prevent Edgar from pushing his usual pace, but he still struggled in the later rounds.

Edgar started landing more consistently late in the third round. Fatigue slowed Aldo’s reactions, and Edgar worked out how to get to him. Instead of blindly rushing into the pocket, Edgar was now using his feints and entries to draw out and punish Aldo’s counters.

While Edgar’s resurgence was not enough for him to win rounds, he at least gave Aldo a run for his money in the later portion of the fight. Unfortunately for him, Aldo would not be dissuaded. Tired as he was, he continued exchanging with Edgar, using his magnificent defense to stymie the challenger’s attacks while landing punishing counters.

The result was a clear decision for Aldo, though Edgar had managed to turn a domination into a close fight through adaptation, heart, and an everlasting gas tank. Aldo took four out of five rounds on two of the judges’ cards, while the other gave him three. Although Edgar cleanly won only a single round, he made Aldo work hard for his victory.

Aldo’s win over Edgar marked his fourth defense of the UFC Featherweight title, and his sixth overall defense of the Featherweight crown that he won in the WEC. A win over a legend like Frankie Edgar in his prime, ranked #9 on our list of all-time greats, is the type of win that builds legacies.

Aldo was already established as a dominant champion and one of the more skilled fighters in the sport, but on the night he faced Edgar, he became something more. He was beginning to cement his place in the pantheon. He was becoming one of the greatest fighters to ever live.

A New Jose Aldo

When ultra-athletic, blue-chip prospects finally capture the title, their career arcs tend to progress along a similar path. The road to the title is filled with quick finishes, brutal beatdowns, and broken bodies, but they tend to mellow out in their championship reign. The focus shifts from proving themselves by mercilessly breaking their opposition to survivability and mitigation. This type of fighter has a natural inclination toward offensive diversity and creativity, often able to run opponents over with little more than sheer physicality if they want to. Those that become truly great, however, start relying a little less on their athletic gifts and learn instead to control the flow of a fight.

In order to attain a title shot, you need pick up wins in impressive fashion, but in order to maintain your title, you simply need not lose. This shift in focus often carries with it a change in fighting style. Highly athletic fighters tend to be active risk takers, which is great for garnering attention on the contender’s path, but less useful for protecting what is already theirs. Often champions will start to pare back their skillset, focusing more on their highest percentage tools and leaving behind some of their more risky tactics. They also tend to invest more effort into developing skills that allow them to control the pace and distance of a fight.

Jon Jones is perhaps the best example of this phenomenon: known for endless offensive creativity and risk taking in his early career, he evolved into a thoughtful, strategic fighter who eschewed risk-taking in favor of nullifying his opponent’s most potent weapons.

Aldo had been a more patient fighter for a while now, but he was ready to complete the transition from young destroyer to patient veteran.

While other striking arts like Boxing, Kickboxing, and Muay Thai have a long history of defensive fighters who specialize in nullifying their opponent’s game, they are much less common in MMA. The overwhelming variety of options in an MMA fight means that defense is necessarily less reliable and offense less predictable. As a result, the metagame has trended heavily toward volume and away from nullifying skillsets. Aldo, however, would buck the trend, becoming the closest thing MMA has seen to a late-career Floyd Mayweather or a Giorgio Petrosyan.

The next challenger for Aldo’s throne was “The Korean Zombie,” Chan Sung Jung, a skilled brawler known for his exciting, fast-paced style. The moniker “Zombie” came from Jung’s tireless pursuit of exchanges and seeming disdain for taking a backward step. Jung was beloved among hardcore fans for his brawling style, which carried him to fight-of-the-year performances in 2010 and 2012.

Aldo sucked all the excitement out of his fight with the Korean Zombie, nullifying Jung’s brawling instincts and turning him into a fighter not only hesitant to exchange, but utterly unable to figure out how to create exchanges. Although the ability to have a boring fight with such an offensive dynamo sounds like an undesirable skill, it means that Jung was forced to fight Aldo’s fight from beginning to end. Fortunately for Jung, Aldo injured his foot early in the fight when he threw a leg kick that landed on the knee, so he avoided taking a lot of damage to his leg.

The fight was notable not so much for what Aldo did as what Jung didn’t do. Aldo’s offense was carefully rationed. Jung’s offense was nearly nonexistent. While nothing gets the blood pumping like a high-paced action fight, there’s also something special about seeing a fighter systematically strip his opponent of all their useful tools.

Aldo took away Jung’s lead hand completely. He set himself up just outside jabbing range, which meant that Jung would need to reach to land his jab. When he did so, Aldo would simply parry it in place or slide a half-step back. When Jung tried to hook off his lead hand, Aldo would pull his head back, making the hook fall short. Jung’s attempts to throw in combination and enter behind the jab were stymied by Aldo’s footwork, as he’d back up and circle off before Jung could enter range. When Jung instead tried to push forward aggressively, Aldo was waiting with sharp counters.

While Aldo’s defense looked immaculate, his sense of cage generalship was even more impressive. Aldo’s defense was always at its most impressive in deep, layered exchanges, but Jung was unable to consistently find these exchanges. He found it not only impossible to hit Aldo clean, but difficult to even make Aldo work hard defensively.

The end of the fight proved that Aldo’s pace was born out of control rather than lethargy. Jung dislocated his shoulder in an exchange and Aldo gave us a brief glimpse of the athletic savage that had dominated his early fights. Aldo delivered a rapid series of kicks to the injured arm before taking Jung to the ground and finishing him off with punches.

Once upon a time, Aldo beat everyone who stepped in the cage with him as if their broken bodies contained the key to a better life. But now that life was his to protect.

Aldo showed similar patience in his next fight against Ricardo Lamas. Lamas took more damage than Jung as Aldo battered his legs and body, but Aldo remained economical in creating opportunities. Lamas forced Aldo to go after him, moving around on the outside and looking to land kicks at a long distance. Aldo displayed a sound pressure game, pivoting on his rear foot to keep Lamas aligned as he cut off the cage and using sweeping strikes to corral his man. Brief moments of aggression from Lamas were extinguished through sharp counters. Lamas was soundly outclassed, but Aldo never felt the need to step into second gear and push for a finish.

To some, it may have seemed like Aldo lost his hunger. That his passion for the sport had died and left a hole of complacency. Fans lamented the death of the unstoppable monster that was WEC Aldo. Where inflicting maximum levels of violence and pain once seemed like his primary goal, now any physical torture his opponents received on his path to victory was simply incidental. The “W” mattered more than anything else.

It was still the same Aldo. He was still that kid from the favela fighting for his food. The only thing that changed was his position. Fighting for sustenance now meant something different.

Aldo was the king. He had his feast, and it would remain his as long as he held that belt. Once upon a time, Aldo beat everyone who stepped in the cage with him as if their broken bodies contained the key to a better life. But now that life was his to protect. His opponents were no longer rungs on the ladder to stability, but mercenaries laying siege upon a structure he’d already built.

If they backed down, Aldo was content to let them go - to sit safe in his castle and starve opponents out until the clock ran down. The way he saw it, there was no benefit to putting himself in harm’s way, risking the title that meant everything to him, just to entertain. When opponents pushed him however, they were seldom prepared for Aldo’s ferocity. Regardless of damage or fatigue, he’d do anything to protect that belt, even if it meant clawing until his last breath. Aldo fought as if he were prepared to die for his belt.

His next fight would remind everyone that the fire was still there. If anything, it had only grown stronger.

Aldo vs. Mendes II

Chad Mendes reinvented himself after losing to Aldo. The Team Alpha Male wrestler developed world-class striking with the help of coach Duane Ludwig. After the first Aldo fight, he won his next five in dominant fashion, finishing four of them. He was no longer a wrestler with a right hand, but a complete MMA fighter capable of excelling in any phase.

The rematch was once again set for Aldo’s home turf, Rio de Janeiro.

It was a fire fight from the opening bell. Mendes immediately made it clear that he was a threat, storming out of the gates with intense pressure. He kicked Aldo’s leg hard twice in the opening minute, showing the Brazilian kicker that he was unwilling to concede any range. Both men threw in combination, using feints to create openings. Both men looked perfectly at home in layered exchanges and actively worked all three levels - body, legs, and head. Never before had MMA seen such a high-level fight.

Aldo was nearly unhittable on the lead, so Mendes hit him on the counter. Mendes mostly fell short on his leads early in the fight, but he was able to consistently find openings as Aldo punched. The wrestler’s defense looked fantastic. His head movement had grown deeper and his reactions sounder. He’d also developed a tight, responsive high guard. Although his defense wasn’t as deep and layered as Aldo’s, it allowed him to stay safe amidst Aldo’s flurries and find openings of his own.

When Aldo threw his rear hand, Mendes would find simultaneous overhand counters, slipping outside the Champion’s offense, or trace lead hooks back to Aldo’s face as his hand retracted. Mendes hit a lovely catch-and-pitch counter a minute into the first round, adjusting his guard down to block an uppercut, before slotting in a quick left hook that caught Aldo on the chin and dropped him. Mendes pursued, but Aldo managed to keep himself safe with impeccable defense.

The rematch with Mendes pushed Aldo to the brink of his abilities, displaying the extent of his indomitable will. Mendes got nothing done for free. After hitting the canvas early in the first round, Aldo received an eye poke with nearly a minute left. He took a minute to rest and stormed back out as if determined to make something happen. He whiffed on a massive combo and stepped into a hard knee, only to be taken down. He stood up immediately and began marching toward Mendes. As Mendes stepped in with a jab, Aldo pulled his head back and landed a ferocious left hook, dropping Mendes and hurting him worse than he had hurt Aldo a few minutes before.

Every time Mendes hurt Aldo, he answered back emphatically.

When Aldo dropped Mendes in retaliation, commentator Brian Stann provided a call that perfectly summed up Aldo as a fighter:

This is the danger. When you want to make the champ work, this is how he works.

After stealing the round with his left hook, Aldo pursued and did it again as the round ended. He threw a buzzer beater combination that landed after the bell and sent Mendes to the floor. The fault for his late shot lied not with Aldo, however, but with the Rio crowd. Referee Mark Goddard explains:

The story of the second round was Aldo’s footwork and straight punching. An active jab kept Mendes on the outside, foiling his attempts to close distance. Aldo layered the jab to the head and body, using it to force reactions out of Mendes and give him ample time to move away. He threw it as an intercepting counter as well, preventing Mendes from stepping in. A long straight right to the body proved another obstacle to Mendes’ distance-closing efforts. When Mendes poured on the pressure, Aldo would pivot away. When he danced around the pocket looking for angles, Aldo would subtly adjust his positioning to keep Mendes lined up.

The second wasn’t all Aldo, however. Mendes landed a gorgeous sequence of counter rights as Aldo stepped in to punch. He slipped a left hook-straight right combination, timing an overhand as Aldo’s right missed. Mendes then shifted forward into southpaw and doubled up on his right hand as Aldo exited the pocket.

The third round progressed in a similar manner - both men found success in exchanges, with Aldo getting the better of most. But halfway through the round, Mendes turned the tide. He faked a takedown, convincing Aldo to change levels in response, and stuck him with a massive uppercut that was aided by Aldo’s own downward momentum. As a stunned Aldo backed off, Mendes followed with a leaping left hook, before shifting into southpaw to close distance with another powerful left hook.

It’s a testament to Aldo’s durability that he managed to take two clean power punches from Mendes subsequently. Mendes pursued Aldo, but only ten seconds later he found himself on the canvas, dropped by an Aldo cross-counter. It wasn’t even that Mendes became overconfident in an effort to finish the fight. It was simply Aldo’s insane composure and determination that got the job done. Mendes remained in position while walking Aldo down, keeping himself within a strong stance and setting up his attacks. He just couldn’t land on the defensively magnificent Aldo. After two fruitless exchanges, Mendes stepped in with a jab and ate a hard right hook on the ear, sending him to his hands and knees.

It wasn’t just the opportunity of the fight for Mendes, but the opportunity of his career, and Aldo snuffed it out as soon as it began.

Mendes came alive in the fourth round. He walked Aldo down while drilling him repeatedly with hooks to the body. He needled Aldo with short jabs and left hooks. Mendes’ non-committal offense with his lead hand was used to set up power punches. He found several hard right hands, using his jab and left hook to set them up, or timing them on the counter as Aldo punched.

Aldo’s volume was dwindling and Mendes was starting to open up. The momentum was tracking toward the challenger after the fourth frame, but Aldo refused to concede the final round.

It’s difficult to overstate how impressive the fight was from both parties. Aldo had faced champions, worthy challengers, and even All-Time Greats, but nobody pushed him like Mendes pushed him. Aldo had never before found himself in a war. Nobody had thoroughly competed with him from bell-to-bell, in every range and phase of the fight. Mendes forced Aldo to display the full range of his skillset and fans were treated to an extraordinary show.

We knew that Aldo had a defensive skillset like nobody else in MMA, but we didn’t know just how deep it went. The usual mainstays were there - he was parrying Mendes’ jab actively, giving just enough ground to make him miss, and slipping punches, but there were new elements as well. He was framing with his hands to jam Mendes’ punches and closing distance to take himself out of the path of Mendes’ hooks. All these tactics were seamlessly integrated into a complete defensive system, allowing Aldo to smoothly chain between them in layers. No matter how deep Mendes forced exchanges, Aldo always had an answer.

While circumstances (and a drug test failure) prevented Mendes from accumulating a resume befitting of his talent, he was one of the best fighters in MMA history on the night he fought Aldo. The kind of fighter who doesn’t even exist at lesser weight classes like Light Heavyweight (205lbs) and Heavyweight (206-265lbs). Pushing Aldo near his limit would remain the most impressive accomplishment of Mendes’ MMA career, and indeed the feat carried more gravity than many historic wins.

This time, Aldo didn’t leap out of the Octagon and bolt into the stands. Before the decision was announced, he sat atop the cage and gestured to the implacable crowd. His posture was that of someone who’d been there before. No longer the excitable young champion of merely two short years ago, now he looked comfortable in his role as one of the greatest to ever live.

When asked if Mendes gave him the toughest fight of his career, Aldo responded:

I think every fight in my career is the toughest fight

It was simply another day at the office for the greatest of all time. He did what he had to do - no more, no less.

King-Maker

In combat sports, legends fall as quickly as they rise. It seems almost a truism to say that great fighters will continue fighting until they decline. While there are many personal reasons a fighter may be reluctant to abandon the sport that brought him glory and (hopefully) wealth, this phenomenon also serves a structural purpose.

Legends are used as fuel to power the next generation of athlete. Nothing drums up excitement for a new contender like impressive wins over the greats of yore. When the older man bows out with grace, it can be a beautiful thing; the passing of the torch from one era to the next, as the old lion teaches the young gun a few lessons along the way. Other times it represents a vile practice of exploitation, as legends fight years after their sell-by date and fans are treated to their old favorites being beat repeatedly into unconsciousness by men who don’t deserve to share the cage with them.