The All-Time Great Bantamweights: No 7: Kid Williams

7. Kid Williams 161-30-12 (49 KOs)

“Williams, a sawed-off Hercules, was a ferocious little fighter - a hard hitter and a terrific slugger.”

So wrote Ed Hughes in 1928 for 'The Brooklyn Daily Eagle'. The reverent tone sounds like an account of a fighter from the early days of gloved boxing, a call-back to a long-lost champion. They wrote about John L. Sullivan the same way.

But when these words were penned, Kid Williams was still slugging. Despite not really holding the bantam title in over a decade, the Dane born John Gutenko was proving himself a rare breed; a little man with longevity. Fifteen of his 19 official losses might have come in the roaring 20s but he still won more than he lost, and was still clawing off scalps worthy of an all-time great.

But it’s the prime years we are really interested in, and from 1912 to 1915 Kid Williams went unbeaten within the bantamweight limit. When he finally saw a tick in the loss column it was a close six-round decision against a man he had already beaten and would beat again.

He won 44 out of 46 in this timespan, a couple of tight newspaper draws the only hiccups and of no concern to us when evaluating his quality. He stopped 18 of these men, and battered everyone who dared last the distance with him. He earns the nickname ‘Wolf Boy’ such is his savagery.

The Kid as a Kid

The kid who was yet to be given that moniker moved to the United States at seven years of age, and first fought on the streets. A newsboy, he scrapped with other lads for turf and beat them so badly he lost his job altogether. Before that he also robbed his customers, running off with their coin when asked for change.

One of those men was Sam Harris, boxing manager.

“That’s the way I met Harris," Kid Williams told 'The Seattle Star' years later when he was in the papers himself. “I sold him a paper and he gave me half a dollar to get changed. I ran away with the half dollar.”

Wanting to teach the rascal a lesson, Harris went back to his patch to find little John Gutenko and dragged him along to the local athletic club to see him get licked by neighbourhood toughs who really knew how to fight. But the kid didn’t get licked, and Harris was inspired to take him under his wing and train him in fistic science.

He’d created a monster.

Williams first found fame as a young prospect in Baltimore. 'The Baltimore Sun' wrote that his rise had been meteoric. No surprise when he went 13-1 in his first year as a pro, the single loss debated by the same publication for a few weeks before deciding on Williams as the loser. In 1910 he could still make 105lbs, but it’s further north where he would make his legend.

Chasing the championship

Despite his quick start to the pro game, Williams would have to overcome knockouts and decision losses and keep improving. By 1912 he was regarded as one of the best bantams in the game, but the champion was not only one of the best little men to ever put on the gloves, but also the most unwilling to actually fight Williams.

Due to the logistics of the day, Williams’ promoter Sam Harris had to go cross country just to discuss a bout between Williams and title holder Johnny Coulon. He had his young charge fight everyone he could, the so-called best bantams of New York and Philadelphia, but the Canadian Coulon was the fighter Williams had set his sights on. Williams made the lower weights as claustrophobic as he could for the diminutive champ.

Johnny Coulon

“Harris has sent Williams against every bantam candidate in the country who has a right to challenge Coulon and the Kid has trimmed every aspirant to the title. Therefore, should Coulon desire to meet any other boy in his division he simply will be stacking up against some boxer whom Williams has defeated”, said 'The Baltimore Sun'.

And they were right.

Not that Coulon was a cheese champion. He had taken his title claim up through the weights and still maxed out at around the modern flyweight limit. Fighting bigger guys was how he made his money, and with only three losses in 67 bouts he was damn good at it.

Coulon had beaten Jim Kenrick, the best British bantam. He also added top Yanks such as Frankie Burns, Patsy Brannigan, Johnny Solzberg and arguable all-time greats Frankie Burns and Harry Forbes to his resume. Forbes was past his best, but although his form might not have been good enough to make him an impressive victory for Coulon, his words still carry weight. He said after the bout: “I had only one chance. That was to land a telling punch at the start. Johnny kept me from landing that right, though I did catch him once or twice. He is a great boy, one of the greatest little boxers that ever lived.”

Forbes would know; in his long career he had faced Terry McGovern, Danny Dougherty, Casper Leon and Abe Attell, amongst the best fighters below 9 stone of all time at this point in history.

All in all, Coulon had 18 successful defences of some kind of world title, be it labelled paperweight or bantamweight, and was highly regarded as one of the best ring generals of the time.

Six months prior to getting Coulon in the ring, Williams was seen as the best challenger to Coulon’s title when he battered Johnny Daly over 15, a fight that was described thus at the time:

“All of the people who are qualified to judge the ability of a boxer agreed at the ringside after the bout that Williams demonstrated his right to meet Johnny Coulon for the championship of the world. Daly did not have a decided advantage in one of the rounds. In the eighth he shaded Williams, perhaps, but even the most broad minded of the regulars were willing to admit that honors were about at a standstill. The second round was even but in thirteen periods Williams displayed a big lead. His one fault was his inability to locate the point of his opponent's jaw. Not once did he touch it during the battle. The Kid landed enough blows on Daly's body to make an ordinary man quit but Daly was no ordinary boy. Then, too, Williams cut and bruised his face, nose and mouth, but all of his blows in that direction were too high to land the sleep.”

Sounds like getting knocked out for the count might have been the better option for Daly.

Six months does not sound like a long time to make a big fight for the modern fan, but consider that Williams fought 11 more times in this time frame. Coulon fought just thrice, the schedule of a contented champion in 1912.

Still, in July of that year Coulon had looked very much the champion. Beating the experienced Joe Wagner in New York City, 'The Brooklyn Daily Eagle' commented that Coulon looked sharp enough that he needn’t have trained, and "it looked as if he could defeat Wagner after a six months’ layoff". Coulon toyed with his man, hitting him hard whenever he tried to force his way back into the fight.

In October, Coulon relented and agreed to defend his title against the man seen as his most formidable challenger. It would only be over ten rounds and with the decision in the hands of the newspapermen. This way, without official judging or the referee as the sole arbiter, Coulon would keep his championship if he stayed on his feet. With his experience and Williams’ accumulative style, this was a safe way for Coulon to risk it all against the young and dangerous challenger.

Coulon was right to be wary. Despite this, he was still favoured to get the better of the upstart Kid from Baltimore.

“Coulon appears to be in particularly fine fettle, for, as he admits, Williams is likely to prove the hardest kind of opponents," read 'The New York Times' preview. “Unlike many first-class boxers, Coulon packs a wallop that has sent scores of bantams to dreamland, and it is because of this combination of skill and strength that his admirers regard him as invincible in his class.”

Williams would prove the Coulon backers wrong.

'The New York Times' headline after the fight stated: "Kid Williams too clever for Coulon" and it was the opinion of the scribe ringside that Coulon only kept his title by virtue of the fight being held in New York. Coulon knew any decision rendered would be unofficial due to the rules at the time.

It is likely that if three judges had handed in their scorecards that Kid Williams would have walked out as world bantamweight champion.

Despite his youth and lesser experience, Williams took the fight to Coulon straight away. Coulon’s ring smarts had no effect on the challenger, who refused to bite on the champion's feints. Neither man was in much distress during the ten rounds - which were a high class exhibition of scientific boxing - and although Coulon got his timing down as the minutes went by, Williams was the aggressor, and his strength and size took a toll on Coulon. The champion resorted to clinching rather than mixing in the last few rounds, and at the end of the ten Williams was seen to have the better of it.

Coulon was smart, though, both in the ring and outside of it. Naturally smaller than the best bantams of the time, he was able to maximise both his chances and his earning potential by dictating the terms of his title fights and adapting to his opponents inside the ropes.

It would be 14 months before Coulon would agree to defend his title against Williams for a second time. The champion - a veteran of 73 fights at just 25 years old - would have five fights in the interim.

Kid Williams would have 21.

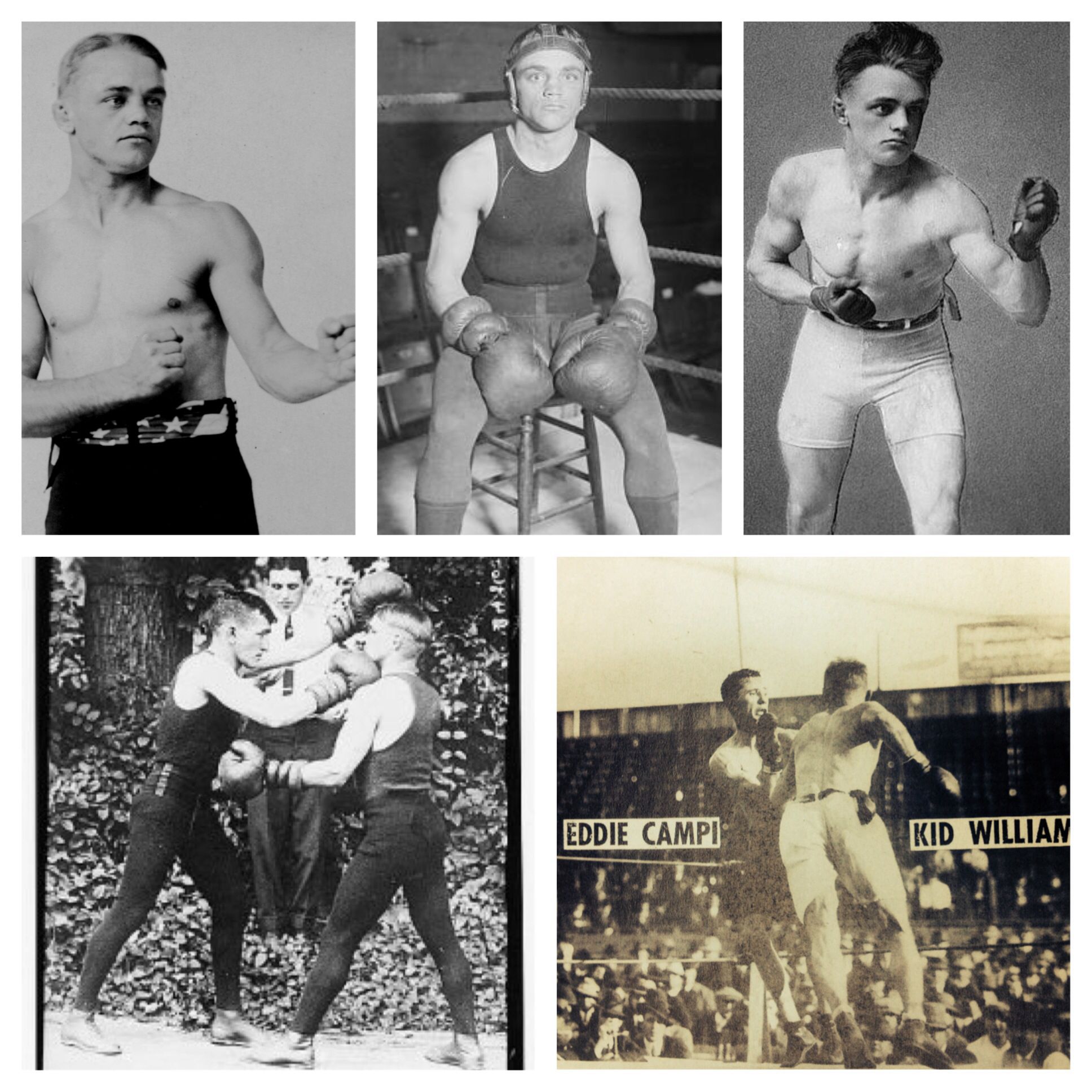

Top Row L-R: Three fearsome fighting poses of Kid Williams

Bottom Row L-R: Williams spars, and Williams with one of his signature rushes at his great rival Eddie Campi

A Fearsome Prime

From his arguable victory over Coulon in their first bout to their rematch in 1914, Kid Williams would go on a run that stands alongside any string of victories by anyone that sits above him on this list. He was that good at his peak, and the horror he inflicted on his opponents from here on out demonstrates that these were undeniably his best years.

Johnny Coulon was wise to give the Kid the slip.

These men didn’t. Another Johnny had a go; the excellent British flyweight Johnny Hughes, a veteran of nearly 200 fights. He had faced every British fly and bantam available in a career reaching back into the 19th century. Another top Brit, Jim Kenrick was as experienced as Hughes. Between them the pair laced up for 400-odd pro bouts.

Frenchman Charles Ledoux, right near the top of any credible list of the hardest punchers under featherweight (he punched above nine stone too) had two chances to put the ‘Wolf Boy’s lights out.

Veteran Patsy Brannigan, who would beat legendary featherweight champ Johnny Kilbane and former bantamweight title claimant Monte Attell.

The superb pure boxer Eddie Campi, bested just thrice in 42.

A varied bunch with a connection; Williams beat them all, some badly.

Eddie Campi might have been the best of these. The first bout between the two went the full 20 rounds, and when Campi claimed the IBU version of the world title by outpointing the aforementioned Charles Ledoux (which was a perilous task for someone with no stopping power like Campi) he and Williams were matched again.

“Campi is fast and scientific to a freakish degree. Critics declare the youth to be the equal of men like Welsh, Kilbane, Attell and [Packey] McFarland”

Kid Williams already had a strong claim for being the best bantam in the world following his fight with Coulon. Against Campi he would have a chance to further legitimise his claim.

Fighting in Vernon, California, much closer to Campi’s San Francisco home than Williams’ Baltimore, this was a classic clash of styles; a pure boxer versus a swarmer.

Before the fight, the press claimed that they were fighting for bantamweight supremacy, at least in Coulon’s absence from the prize ring due to a stomach ailment.

In their first fight the year prior, Campi was favoured, his lightning left hand and size the likely difference maker.

'The Sacramento Union' report gave Williams credit for his form, but didn’t see him as the potential winner:

“Despite Williams’ victory over Coulon in New York and his defeat of Ledoux, the French champion, the San Francisco boy has been made a slight favourite because of his superior height and reach. Campi is more than five inches taller than Williams, who measures but 5 feet 1 inches."

Campi managed to use his gifts to evade his aggressive opponent enough to survive the full 20, but Williams won ‘clean’ according to one source. He was lauded for his all-round skill set and the pace he set.

“Williams impressed the fans with his class and made even a greater hit than did Coulon when the bantam champion made his (West) coast debut a few years ago," read a 'Los Angeles Herald' report after the fight. “Williams is a greater piece of fighting machinery and probably would whip Coulon when the latter was at his best. He is a happy combination of speed, cleverness and punch, and he looked all over a champion.”

After Campi beat European champ Ledoux he claimed himself a world champion. French-based boxing board the IBU gave him their championship, and he gained rave reviews for his boxing ability.

“Campi is fast and scientific to a freakish degree. Critics declare the youth to be the equal of men like [Freddie] Welsh, [Johnny] Kilbane, [Abe] Attell and [Packey] McFarland,” gushed one writer. This was very high praise indeed, and if indicative of Campi’s ability he must have been a top-class operator.

He might have survived the devastating Ledoux, but he fared even worse against Williams in their second go. The early rounds were even, with Campi gaining an edge in a few of the rounds, but he had no answer for Williams once the distance was closed. Williams charged his man at the start of the 12th and folded him with a nasty whack in the solar plexus. Campi didn’t even get the respect of the referee’s count, which says a lot for this bloodthirsty era. He later claimed a foul, but the post-fight reports credit Williams for his excellence. He was described as “a heavyweight cut down to bantam size”.

Campi then moved up to featherweight, leaving only one man in the way of the Kid becoming the King of the bantam division.

The Unified Champion

With the advent of the internet, easily accessible fight footage and the minutiae of every fighter's training camp and career is there for us all to see, and we are thus able to judge the quality of a champion in more depth than ever before.

With the old timers it is sometimes a little dicier. It’s easy to look through the records of fighters and assume they’re either superheroes or bums, but digging into the story behind these paper records can often illuminate a fighter once more details are amassed.

Or cast a shadow on them, as it does in the case of Johnny Coulon.

Inactive, fighting above his very best weight, and being troubled by a long-term stomach illness, Coulon was talking the talk going into his rematch with Kid Williams, but was he walking the walk?

The ‘champ’ still felt he had it in him, announcing he was “ready for the 'come back': that he was cleverer and stronger than ever, and that he wanted to be pitted against one of the many fast boys who have sprung up in his division”.

'The Racine Journal News' covered Coulon’s warm-up bout prior to his big rematch with Kid Williams, and put Coulon’s form into perspective. This was not some champion in his prime, despite the fact he had never been knocked out and was still clinging on to his championship claim:

“Before the flickering gleam of another dawn Johnny Coulon, erstwhile bantamweight, will be lauded as one of the niftiest little 'come back' artists in the history of the padded square, or else be relegated to the archives of memory.”

The article went on to describe Coulon’s last fight - some six months before - as Coulon’s worst showing. That was a draw against top drawer Frankie Burns, with Coulon turning in a performance that “stated broadest that Johnny’s days as a pug of the first order was over”.

Johnny Coulon was one of the premier little men of the 20th Century

In Racine he would fight a youngster from Chicago called Francis Sinnett, with an impressive-looking 16-1 record but no opponents of note to his name. A decent test for a fighter apparently past his best, but one that Coulon should have come through unscathed. And Coulon had already said he felt as good as he did in his prime, if not better.

Coulon was clearly far and away from that level though when Sinnett whipped him in ten fast rounds. Coulon looked good in the early going, dancing around the ring and making Sinnett look clumsy. In the seventh, Sinnett “nearly landed a knockout with a hard left to the jaw”, and although Coulon tried desperately to knock out his younger opponent in the final round, the local paper felt Coulon had won only two total rounds. 'The Milwaukee Free Press' gave it to Coulon, but he had clearly slipped from the form that had seen him fend off all comers just a few years earlier.

So it should be of no surprise when Kid Williams mopped the floor with him five months later. This time Williams was the favourite, and he drubbed the Canadian before three rounds were up. In reality Coulon was finished in the second, but a series of smashing blows in the third had Coulon first halfway out of the ring and then barely able to get back to his corner when Williams was proclaimed the winner.

No one could doubt Kid Williams as the best bantamweight in the world after this. And if you give him credit from the first Coulon fight, his reign is a mightily impressive one.

But as the rules stipulated that only a finish would see the title change hands, Williams’ actual championship reign was not all that impressive. An one-sided win against a not quite prime Pete Herman adds to Williams’ bantam legacy, but he failed to put a stamp on a later 20-round draw with Herman, or the excellent Frankie Burns, which saw the same result. Fighting on even terms with bantams this good adds to his appeal though, and Williams was still earning rave reviews for his showings.

Like Coulon before him, Williams’ own title claim would become mired in controversy when he was disqualified in what should have been a routine title defence against the world class Johnny Ertle. Both men claimed championship status after the bout, and would fight twice more. Williams was the better man overall, but in the wake of this a more talented bunch of bantams rose up to snatch the kingdom from him.

Kid Williams would continue to fight in, around and above the bantamweight limit for well over a decade after his championship exploits. He is undoubtedly one of the greatest fighters the bantam class ever had in its ranks, and perhaps with a chance to claim the championship proper a few years before he did he might rank even higher.

Taking into account his ferocious run to the title, and the fact he fought on even terms with some of the great fighters that followed in his wake, there are not many that sit above him here.

In 1928, when Ed Hughes looked back on Kid Williams' career, the former champ was still the talk of the town back home in Maryland.

In the midst of another climb towards the top of the mountain, Williams’ comeback was described as remarkable and he was seen by the press as taking on all comers with more than average success. It didn’t work out for him, but he showed enough glimpses of the wolf boy of old to make youngsters fill their pants.

He was nearly 40, not only ancient in his own era but a fossil in any time and place for those campaigning in the lower weights.

Remarkable as it may have been, it’s not too surprising though either; Kid Williams was as pure a fighting force as has ever been seen among bantams.

The next legend on this list has one of the trickier title reigns to assess. Not that you would ever believe it looking at the astonishing numbers he put up.

This article was originally published on boxingmonthly.com and was edited by Luke G.Williams. You can purchase Luke’s excellent book Richmond Unchained here